Galit Eilat, Erden Kosova and Jelena Jureša

in What Was Happening Here Was Never Normal Anyway

Versopolis/Review

2020

Erden Kosova: Jelena, the title of your comprehensive video piece from last year is quite intriguing: “Aphasia”. When we were going through your previous work, we came across your academic thesis entitled along the lines of: “Unfolding Amnesia”, “Oblivion ”. These are familiar terms to us. However, Aphasia was unfamiliar: I had to look at a dictionary to know more about it. Perhaps you could give a short description of the phrase and a glimpse of how it plays out throughout the film.

Jelena Jureša: Aphasia is a medical term for the condition in which a person is unable to formulate clear sentences, or loses the ability to speak. While writing about French colonialism, Ann Laura Stoler coined the term “Colonial Aphasia”, referring to cognitive failures to deal with the troubled past, describing the problematic relationships which European nations hold to their colonial histories. She puts at the centre of the debate the occlusion of knowledge, referring to the fact that we perceive historical violence as compartmentalised and distant, without perceiving its rhizome-like structure.

My intention in Aphasia was not to connect things in a documentary fashion, but to make a sort of documentary gesture, a rhythmic score: to show the structure of this cognitive failure as a tapestry of relations. Hence, to look at the history of Europe through its historical oblivion. And there is also the question of implication, the question of positionality within this structure — not only of my implication, as an artist dealing with these topics — but also the complicity of the media, film, and photography, which evolved from being a mechanical reproduction tool to an agent for recording, coding, and decoding.

Galit Eilat: Aphasia is an essay in time which employs poetic language over knowledge which is not easy to swallow. When did you start to work on the film and how long did it take you to make it?

JJ: Having been raised in Yugoslavia, and continuing to live in Serbia after the war, in a state practising distressing politics of oblivion regarding its war crimes, it has been inevitable that I critically reflect in my art practice on the conscious forgetting taking place in the region. The sobriety of the approach requested that I study and understand certain phenomena through historical, sociological, or psychological contexts. Having moved to Belgium almost six years ago, I started to focus on and to analyse the mechanisms of the politics of oblivion in the broader European context, which expanded my research and opened up the way in which I conceptualised Aphasia.

EK: The first quarter of the film is composed of scenes that retrace the horrible deeds of the colonial system: subjugation, exploitation, homicide, and even claiming the corpses to exhibit them as treasures. The collective memory of Western Europe is kept alive, well-protected between the walls of “the museum”.

GE: This is why we created museums, right? What we see there are looted objects and trophies. So, the museum is hiding the violence behind the objects. Furthermore, this is an institution that is supposed to activate the memory. Who needs to remember what? What kind of memory and to whom does it belong? We can say that the process of decolonisation of museums already started in the 1940s during World War II. From where did they get their collections? Not from Benin or a similarly exploited geography. They got it from neighbours or neighbouring countries.

JJ: The legacy of museums and art institutions is a colonial one. The Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, where the shooting took place, describes itself as the “last colonial museum”. I found the idea of having the Africa Museum in Belgium disturbing. The filming of empty dioramas and the taxidermy collection took place during a period of museum renovation. Seeing these “animals” without any taxonomic order was enough to capture the gesture of epistemological chaos.

GE: With the interplay between these dreamy moments and sudden shifts and crescendos in the voice of the narrator, along with unexpected changes in geography and time, you maintain a sense of command over our attention.

EK: This voice, identifiable as white and male, a coloniser’s voice, flows between different languages of Western Europe: English with a British accent, German and Italian. And the audience listens to the way in which this voice gradually undoes itself. Besides the intended impression of getting mad, perhaps this shift in the narrator’s voice from a sober tone to a quite expressive delirium hints at failure, the realisation of his past mistakes, sarcasm that displaces this privileged subject’s own self-assuredness, the possibility of self-critique.

JJ: The idea was to use this liberal trope: a male voice familiar from documentary filmmaking, a voice we all trust. The narrator uses the knowledge that already exists and jumps from one historical reference to another. The actor was instructed to assume an imperial, colonial mindset derived from a position of entitlement — as if he were entitled to everything. Still, he had the role to build his (vocal) performance to a point where the story can’t hold together anymore. This voice itself becomes aphasic, in which his language fails him. Slowly, he becomes mentally unable to assess things in a particular order.

When I was working on Aphasia, I was working on dramaturgy and not the script. Beckett’s performances were a lot on my mind. In his piece “Not I”, there is only a single mouth on the stage, uttering an excess of words randomly, not being able to follow the thinking brain. When I was composing the performance of the narrator in the first act of the film, I followed this pace in which the brain operates faster than the possibility of pronunciation. Brecht and Beckett were useful tools to frame his act. So, I had the intention of destroying the male narrator. However, for me, the crucial question to pose was: are you (as the audience) more irritated by his composed tone in the beginning, or by his tone later on, drifting into madness?

EK: There’s a morphing effect, a gradual spinning of intrinsic rhythm between the parts of the film, in which a cinematic tension is built up towards the end. The first half prepares a grounding of contextualisation for the audience and weaves an argumentative line between different realities and time periods. Then the second half of the film is narrated from a subjective perspective, which is based on the actual, traumatic events of one of the first pogroms in Bosnia. And the film ends, perhaps, with the bodily expression of the unspeakable.

JJ: The rhythm of the dramaturgy was not based on the usual linear narrative you would find in documentary practices. I rather had music in mind when I was working on the structure, and I wanted to follow thinking that would run parallel to sound and image, where they would meet at certain points, run together and then diverge from each other.

GE: In the end of the first half, we see a young boy eating an apple. It reminds me somehow of a sentence from the bible: “The fathers have eaten sour grapes , and the children’s teeth are set on edge”. The ancestral sin, which has consequences on the next generations. Maybe this is my interpretation of the boy biting the apple in amok. And then we see a pile of rotten apples. The relation between the one rotten apple in a box, the rest that are just fine, and the excessiveness of biting “the fruit of the tree of life” or the “fruit of knowledge”, creates a beautiful and moving moment.

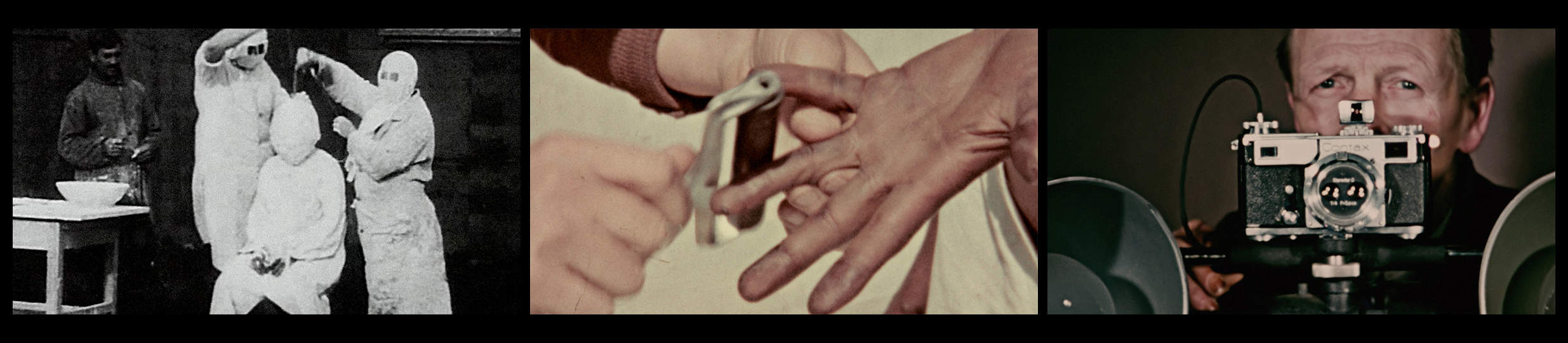

JJ: It is about the genealogy of violence. The first racial experiments that we see in the second act of the film are led by Rudolf Pöch, who conducted his anthropometric studies on war prisoners in camps situated in Austria-Hungary and Germany during WWI. Pöch was an anthropologist and racial hygienist and is also considered a groundbreaking media pioneer in photography, cinematography and sound engineering. The camps provided an opportunity to further his studies on a wide range of ethnic groups, and to validate previous research, such as racial cataloguing and typecasting. Later on, Pöch’s student Josef Wastl, the head of the anthropological department at the Natural History Museum in Vienna, reinforced these experiments on war prisoners with a camera, hence a new medium of colour film. He passionately filmed those kids devouring apples, and I can assume that the kids were instructed to eat the apples in that violent manner for the camera. The scene has a resonance with another one in the first act, in which a crocodile is violently killed in front of the camera, for the sole purpose of filming this violent act.

EK: The second half of the film is marked by a female presence. First, we see a very eloquent woman talking, in an apparent psychological tension, about a war crime — a specific person who was involved in it and his afterlife as a DJ in the Belgrade techno scene. Then, we see the dance of a female figure who traces the bodily gestures of the fascist male body of a soldier who later transformed into a DJ playing at raves. What could be the intention of this dancer reenacting the moves of a war criminal? To absolve from the burden of a past trauma? To remind us of the fact that past crimes have remained unpunished and still haunt the present? I read it as the refined and calculated speech of the first woman coming to the limit of the speakable: the moment when she accidentally engages in a brief conversation with this guy. At that point, a second woman, the dancer, picks up the endeavour and intervenes with her body and movements.

JJ: In the third part, we see a journalist, Barbara Matejčić, as she contemplates, almost scrutinises her encounter with the former soldier, also known as Max during the wars and today as DJ Max. Today he performs in Belgrade night clubs, and during the war, DJ Max was a regular in the club called Industrija — in which, during the 1990s, people opposing the Milošević regime would gather. Barbara and I were curious about whether the people at the club knew this at that time. She started her research, and we almost obsessively focused on every detail we could find about him. Apart from interviews that Barbara conducted in Belgrade, we went through the transcripts and video images from the Hague Tribunal, where his identity was confirmed in two juridical processes.

Keeping Arendt’s notion of “banality of the evil” in mind, Slavenka Drakulić wrote a book, They Would Never Hurt a Fly, after following the trial sessions at the Hague tribunal. As Drakulić herself notes, the entire project was constructed out of the need to revisit and understand the process and the reasons for the breakup of Yugoslavia. Through the book, she is searching for an answer to the question of what is it that turns a pleasant individual, the kind neighbour, into a criminal. And she notes that if we believe that the perpetrators are monsters, it is because we would like to separate “us” from “them”. For me, the notion of implicitness was something to ponder on and play with. Lastly, I would say that when it comes to perpetrators and victims, I try to go beyond this binary relationship. Therefore, while talking about perpetrators, I want to point at society itself. The case of DJ Max is remarkable because the Serbian state was directly complicit with his crimes, as he was on the payroll of the state’s Secret Service, as were other soldiers from the Serbian Volunteer Guard, a.k.a. Arkan’s Tigers. So who would you put on trial in that case? Where is the line between them and us, the guilty ones?